Chaos Theory, Jung, and the Structure of Story

Using Nonlinear Dynamics and Jungian Psychology to Trace the Contours of Narrative

“We are our choices.” — Jean-Paul Sartre

“It is our choices…. that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.” — J.K. Rowling

“We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.” — E.O. Wilson

We all make choices every day, big and small. We tell ourselves and each other stories about what those choices mean. Usually, the stories take either prescriptive (do this) or cautionary (don’t do this) form. If they don’t, there is this unspoken sense of “cool story”, but a rather let-down feeling on the side of the receiver of such a story. What if advancements in nonlinear dynamical systems research can illuminate the psychology of our minds, which in turn frames the contours of the stories we tell ourselves?

Strap in.

Nonlinear List of Some Relevant Science Terms

These definitions are good for humans to know, because they describe so much of our modern world— whether we think of it as VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) or BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible).

Chaos theory: The field of study in mathematics that studies the behavior of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions—a response popularly referred to as the butterfly effect. Small differences in initial conditions (such as those due to rounding errors in numerical computation) yield widely diverging outcomes for such dynamical systems, rendering long-term prediction impossible in general.

Nonlinearity: A property of mathematical functions or data that cannot be graphed on straight lines. A nonlinear system is one whose output(s) are not directly proportional to their input(s), objects that do not lie along straight lines, shapes that are not composed of straight lines, or events that are shown or told out-of-sequence. It is the feature of natural (real world) or other systems which cannot be decomposed into parts (additivity) or reassembled into the same thing (replicability).

Strange Attractor: In the mathematical field of dynamical systems, an attractor is a set of numerical values toward which a system tends to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions of the system. System values that get close enough to the attractor values remain close even if slightly disturbed.

Dynamical System: A system whose state is uniquely specified by a set of variables and whose behavior is described by predefined rules.

Complexity Theory: Complexity theory is an interdisciplinary theory that grew out of systems theory in the 1960s. It draws from research in the natural sciences that examines uncertainty and non-linearity. Complexity theory emphasizes interactions between agents and the accompanying feedback loops that constantly change systems. While it proposes that systems are unpredictable, they are also constrained by order-generating rules.

Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS): A collection of relatively similar and partially connected micro-structures formed in order to adapt to the changing environment and increase its survivability as a macro structure. They are complex in that they are dynamic networks of interactions. They are adaptive in that the individual and collective behavior mutate and self-organize corresponding to the change-initiating events. Examples of Complex Adaptive Systems- insurgencies, economic markets for goods, vehicular traffic flows, ecological systems, and the illicit drug trade. Humans are also Complex Adaptive Systems at the individual level.

Self-Organization: A process where some form of overall order or coordination arises out of the local interactions between smaller component parts of an initially disordered system.

Path dependence: The set of decisions one faces for any given circumstance is limited by the decisions one has made in the past or by the events that one has experienced, even though past circumstances may no longer be relevant.

Emergence: A process whereby larger entities, patterns, and regularities arise through interactions among smaller or simpler entities that themselves do not exhibit such properties.

Agents: Actors that have agency, which is the capacity to make choices and act on those choices, according to some sort of ruleset.

Coevolution: cases where two (or more) species reciprocally affect each other's evolution. So, for example, an evolutionary change in a plant, might affect an herbivore that eats the plant, which in turn might affect the evolution of the plant, which might affect the evolution of the herbivore...and so on.

Feedback Loops: The qualitative dynamic behavior of nonlinear systems is largely defined by the positive and negative feedback loops that regulate their development, with negative feedback working to dampen down or constrain change to a linear progression, while positive feedback works to amplify change typically in a non-linear fashion.

Systems Thinking: A discipline for seeing wholes and a framework

for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static snapshots.

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum and alternating current, the beating of the human heart, business cycles, predator-prey population cycles, the vibration of musical strings, the firing of nerve cells.

Transition: A phase transition may be defined as some smooth, small change in a quantitative input variable that results in a qualitative change in the system’s state. The transition of ice to steam is one example of a phase transition. Example: the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly.

Not all Nonlinear or Dynamical systems are Chaotic, but all Chaotic ones are Nonlinear and Dynamic

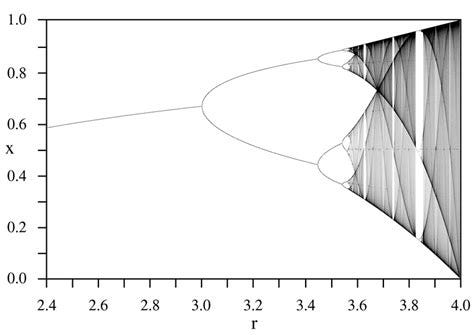

This is a really interesting video showing the Hopf Bifurcation/Feigenbaum Constant, courtesy of Hanzi Freinacht:

Period Doubling Cascades Found in Oscillating Systems

Logistic Map Discovered by Biologist Robert May

Jung and the Unconscious

In Archetypes and Strange Attractors: The Chaotic World of Symbols, clinical psychologist John R. Van Eenwyk, discusses the role of symbols, and their part in aiding the subconscious to make sense of the world. He takes this idea of bifurcations and oscillations from chaos science and applies them to humankind’s ability to navigate their lives. A graduate of Chicago’s C.G. Jung Institute, Van Eenwyk discusses how the new science has affected Jungian Psychology, exploring the link between the dynamics of symbols in the psyche and of chaos in the world of matter. Jung defines archetypes as “deposits of the constantly repeated experiences of humanity…. a kind of readiness to produce over and over again the same or similar mythical ideas…recurrent impressions made by subjective reactions.” From the introduction to the book:

“Jung believed that very few symbols always have the same meaning. Perhaps foremost among these is the ocean, which he considered the universal matrix from which all life developed. As such, it symbolizes the deepest layers of the unconscious, from which spring the complexities of our personalities. Like the human psyche, however uniformly water behaves, however constant the oceans appear, their dynamics are virtually unpredictable. Every wave, every interaction between waves, is actually chaotic.”

Van Eenwyk (And here this whole time I thought my name was hard) discusses an old Iroquois story, “The Stone Coat Woman” which I have been endeavoring to get an electronic copy to link to, thus far with no success. I will continue to haunt First American scholars until I find one, like a vengeful spirit. It’s wild that I can find traces of it, like this and this, but can’t find the actual story. It’s 2023! This is supposed to be the pre-apocalypse time when we should be able to find everything! Van Eenwyk distinguishes between deterministic vs. entropic chaos—the former we can make probabilistic predictions about, the latter which we cannot. One more excerpt:

“For all folk tales and myths, engagement and relationship must occur before anything new appears. It is the same for symbols. Without someone with whom to engage, symbols do not exist. For Jung, growth is impossible without interactions among the various dimensions of the psyche. For chaos theory, symmetry is impossible without bifurcations and cascades. Without relationship, deterministic chaos cannot appear, for self-similarity enters entropic chaos when it resonates in something else; that is, when it oscillates. It is likely that the same is true of the psychic realm: order occurs when the chaos in one of the dimensions is matched by chaos in another. If so, a primary lesson of folk tale and myth may be that if one wishes to transform entropic chaos into deterministic chaos—at least in the realm of the psyche—one must make it fractal.”

Fractal Self-Similarity of a Coastline

Snowflake Method of Story Creation (Click to access the Fractal Snowflake Story Method)

The concept of fractal attractors suggest that chaos theory shares a good deal of commonality with Jung's theory. That fractal attractors permeate nature and natural processes aligns with Jung's premise that there are patterns in the psyche at birth. Chaotic dynamics are currently being tested for their ability to regulate organic process, such as heart beats, and promise intriguing insights that may illuminate Jung's concept of self-regulation. There are many more commonalities that Van Eenwyk identified between the science of chaos and analytical psychology in the book, a big takeaway is that what seems chaotic is in reality much healthier for humans than we commonly suppose.

The best human tales—the ones that stand the test of long years, are fractal, exhibiting self-similarity at different levels. During key moments there is an oscillation, where things can go different ways. And these key moments are when the Arena speaks to the Agent, and how the Agent chooses to exercise their Agency in response.

Chaotic Bifurcations and Story Structure

This leads me to the concept I’d like to discuss here, which is the interesting similarities between dynamical systems (Examples of dynamical systems include models of population growth, the motion of a swinging pendulum, the variations of a heartbeat, and the flow of water in a pipe.) and the progression of narrative in story. I first became interested in Chaos theory the day I eagerly devoured Jurassic Park when it came out in the 90s. I’d forgotten that author Michael Crichton structured the book overtly in the iterative form I am going to discuss below.

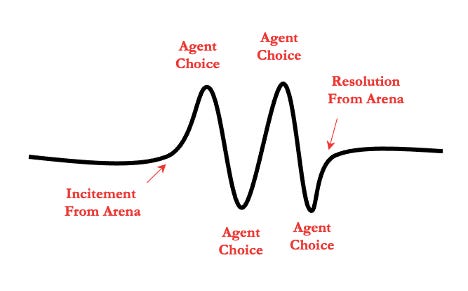

Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid model employs “Five Commandments of Story” or 5 Cs, which scale fractally to describe the flow of story. The 5Cs help the author guide the narrative flow at the global, act, and scene level. Most modern-day story structures follow a three-act format, with Act One comprising approximately 25%, Act Two 50%, and Act Three 25% of the overall story. Story Grid breaks it down into four quadrants which are roughly 25% each—Beginning Hook, Middle Build Up, Middle Break Down, and Ending Payoff. In the Story Grid model, there are 5Cs in each for the four quadrants, for a total of 20 “skeletal” scenes.

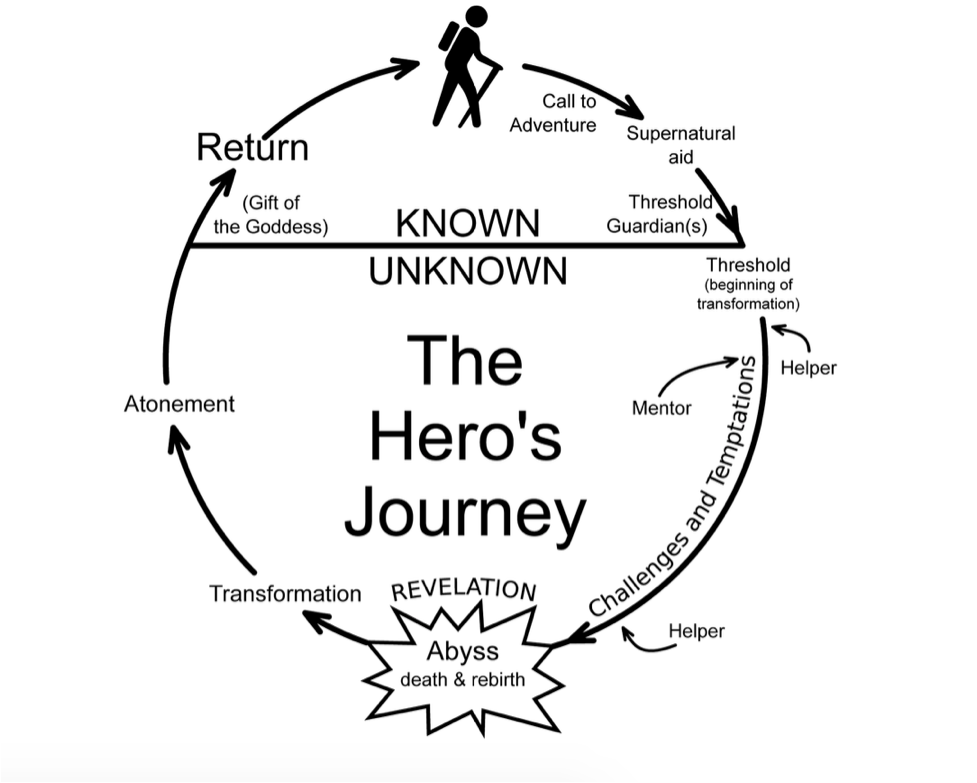

For the purposes of this analysis, I am going to primarily frame this bifurcation sequence against the Story Grid 20 Skeletal Scenes method of structuring a story. However, I will also include my best approximations as to where they fall within Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat!, and John Truby 22 Steps models for those not familiar with the Story Grid methodology. The definitions below for the bifurcation points are the way that Coyne frames the story points.

To quickly recap, the “Five Cs” of story are: Inciting Incident (The event which perturbs the status quo and kicks things off, Turning Point Progressive Complication (When the primary character realizes their default tactic or course of action is not working), the Crisis (The dramatic question), the Climax (Actually making the crisis choice, and the Resolution (The outcome of the choice, which sows the seeds for the next set of commandments). Here’s how that looks overlaid across 4 quadrants:

Story Grid 20 Skeletal Scenes Model

Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey Model

Blake Snyder Save the Cat Story Model

John Truby 22 Step Story Model

The six main bifurcation points I propose are listed below:

First Bifurcation—Story Inciting Incident—Some event or action from the natural world upsets the balance of the world for the protagonist. This is also the Global Inciting Incident. Hero’s Journey- Call to Adventure, Save the Cat- The Catalyst, Truby- Inciting Event.

Second Bifurcation—Beginning Hook (Q1) Climax: The protagonist makes their choice, which impacts both their local environment and the overall story setting. Their location changes from the ordinary to the extraordinary world. Hero’s Journey- Crossing the First Threshold, Save the Cat- Debate, Truby- First Revelation/Decision.

Third Bifurcation—Middle Build Up (Q2) Climax: This story choice is an expression of the character’s ability to tune into the “good,” meaning how well they are making sense of the signals from the unfamiliar environment. If they are making good sense of them, their choice will aid in their transformation. If they aren’t making sense of them, their choice will hinder their transformation. Hero’s Journey- Approach to the Innermost Cave, Save the Cat- Midpoint (False Victory or Defeat), Truby- Second Revelation/Decision.

Fourth Bifurcation—Middle Break Down (Q3) Climax: This is a transformational positive or negative response to the global inciting incident, an expression of the character’s ability to tune into the “truth,” meaning how well they are making meaning from the patterns of signals from the unfamiliar environment. If they are deriving the truth, their choice will enable their progressive transformation. If they aren’t deriving the truth (clinging to falsity), their choice will be regressive. Hero’s Journey- The Reward, Save the Cat- All is Lost/Dark Night of the Soul, Truby- Third Revelation and decision.

Fifth Bifurcation—Ending Payoff (Q4) Climax: This is the transformational progressive or regressive response to the impact of the global inciting incident, and also serves as the global climax. The fourth quadrant climax results in the protagonist’s transformation creating a transformation in their group and ultimately the larger world (Prescriptive tale), or the protagonist’s regression and the regression of the group and the world (Cautionary tale). Hero’s Journey- The Resurrection, Save the Cat- Executing the New Plan, Truby- Moral decision.

Sixth Bifurcation—Story Resolution: The response from the natural world to the choice(s) of the protagonist. The fourth quadrant resolution (which is also the global resolution) will confirm the progression or regression of the avatar’s fittedness to the signals transmitted to them from the world. If the avatar is well attuned and making sense, the avatar will be rewarded. If the avatar is ill attuned and not yet capable of making sense, the avatar will be punished. Hero’s Journey- Return with the Elixir, Save the Cat- Final Image, Truby- New equilibrium.

Taken together, these six events create seven different states for the individual, group, or system over the course of the narrative.

Flow of Narrative through Chaotic Bifurcations from Status Quo to New Equilibrium

Chaotic Bifurcations/Oscillations as Applied to Story Structure

Flow of Narrative and Agent (Re)Attuning to the Arena

Here’s a quick analysis of the narrative flow within that timeless holiday classic, Die Hard, showing the 7 states and 6 bifurcation points:

(1) Status Quo: John McClane is estranged from wife. He heads to Los Angeles in hopes of reconciling with her (Beginning of Film).

(2) Story Inciting Incident: Baader-Meinhof/Red Brigade adjacent group takes over the Nakatomi Corporation building, led by one of the greatest villains in cinematic history, Hans Gruber. John escapes upstairs without his shoes (:17 mark).

(3) Q1 Climax: John wrestles with Tony down a flight of stairs, and Tony is killed in the process (Karl’s brother, :35 mark).

(4) Q2 Climax: John hurls a dead body down on Al’s police car, getting the outside world involved in the hostage situation (:52 mark).

(5) Q3 Climax: In a shootout with group of the hostage takers, John escapes, but loses detonators in the process (1:35 mark).

(6) Q4 Climax: John battles with Hans, culminating in Hans falling to his death (Vaya Con Dios, Alan Rickman, 1:59 mark).

(7) Story Resolution: Final Scene when Al kills Karl when he comes back to life, completing his character arc in the process. New Equilibrium state with wife and family (2:03 mark).

Conclusion- What does this do for us?

The science of Chaos shows us that some of the processes and interactions of our lives, which may seem tumultuous and uncomfortable on the surface, are actually beneficial for our overall health—each of us as individual Agents/Complex Adaptive Systems, and within our larger human groupings. Advancement in the understanding of nonlinear dynamical systems can illuminate how humans process and navigate the complexity of their lives. In turn, this informs the shape of the stories mankind tells itself—what they include and leave out as prescriptive or cautionary scaffolding for the generations to come. This scaffolding is the supreme invention of humanity, the psychotechnology that aids in weathering our sometimes stormy existence. From chaos, order—Ex Chao, Ordo.

Source Material for This Work

· Participation in the Story Grid Guild and the cumulative work of Shawn Coyne. Overview of “The Architecture of a Masterwork” here.

· Metamodernism and Chaos Theory—Hanzi Freinacht. Connects the evolution of Metamemes and Complexity through the Feigenbaum Constant.

· “Archetypes and Strange Attractors” by John R. Can Eenwyk. Discusses Jungian psychology through the prism of Chaos Theory.

· Overview of Hopf Bifurcations.

· “Chaos Theory as a Model for Life Transitions Counseling: Nonlinear Dynamics and Life’s Changes” by Cori J. Bussolari and Judith A. Goodell.

· The work of mathematician Steven Strogatz, to include Sync and Nonlinear Dynamics & Chaos.

I believe the Stone Coated Woman was a single story adapted from multiple stories of the Stone Giants shared among the Iroquois/Seneca. The Buffalo Historical Society printed a book in 1923 with the title - Seneca Myths and Folk Tales and in it. They speak of The Stone Giants - as magical man like beings: "The Stone Giants, or Stone Coats, are commonly described in Seneca folk-tales. They are beings like unto men, but of gigantic size and covered with coats of flint. They are not gods and are vulnerable to the assaults of celestial powers, though the arrows of men harm them not at all. They early Iroquois are reputed to have many wars with them, and the last one is said to have been killed in a cave." Further, Chapter 53 is the story: Beyond-The Rapids and the Stone Giant in which appear the stone coated women.

This post is wonderfully complex and will require (and is worthy of) further digestion. I look forward to rereading later. The point I made in my post today (Think. Read. Write. Repeat) about the reticular activating system was once again proven out when you mentioned the hero's journey. Thanks for your writing!