On a sweltering summer day in 2001, members of GOLF Platoon, SEAL Team FOUR crept down the main hallway of the Left House at the Mid-South Institute of Self-Defense Shooting, in Lake Cormorant, Mississippi. I don’t even think the Right House had been built at this point, but no matter. As a new meat, it was the first time I had trained in Close Quarters Battle (CQB).1

I was overwhelmed.

I found myself stacked up outside the last room on the left, just before the T-intersection. At a nod from my teammate, I opened the door.

He smoothly crossed the threshold, boots crunching on the pebbled gravel at our feet. Following close on his heels, I swept my M-4 rifle left to right and engaged a paper target hung in a stand on the far side of the room.

I didn’t notice my teammate sucking back from my rounds, which slapped into the target a few inches in front of his rifle muzzle.

The lead instructor of the training block pulled me out after the run and gave me a written safety violation. Because the room was “corner fed”— meaning the entrance is in a corner instead of the middle of a wall—I should never have engaged that target from my position.

I almost shot one of my teammates because I didn’t understand what kind of room we were in.

That lead instructor came within a whisker of sending me home from training. I was fortunate the senior enlisted leaders at the Team were willing to give me another chance.

I made a lot of mistakes that first CQB training trip. I think it was my processing speed—I was behind my peers in picking up the basics of a complex skillset. To be fair, it’s a lot to learn.

Good CQB is partly executing the fundamentals of good soldiering— shooting, moving, and communicating, and partly an intuitive art. In less than three seconds, you must take in a mental snapshot of a room, safely manipulate your weapon, clear your fields of fire, and understand both your next best move and the moves of your teammates, all in a very dynamic environment.

You’re entering a hostile building, eliminating threats, keeping your teammates safe, and protecting noncombatants. Accomplishing a checklist of items, while artfully adjusting to your partners and changing environmental nuances.

A nice blending of left and right hemispheres— reducing and abstracting details, and then seeing the overall gestalt. That’s the other part— there’s an art to it, in addition to the science.

I like to use Craft to describe something in between Art and Science.

It’s just like pickup basketball, is a common refrain of CQB instructors. I have never played basketball outside of gym class, so this wasn’t super helpful.

Despite my ignorance, it is like pickup basketball. You’re reading and reacting to the body language and movements of your teammates at a nonverbal level.

It’s also not unlike a jazz group riffing. Your small group is innovating within set parameters. Simple rules2 create an emergent process, greater than the sum of its parts.

The Kill House is an industry term for the place where you train CQB. They usually come with ballistically rated walls and configurable interior floor plans to allow for different scenarios. Our modern agoge.

This video should give you a sense of it. Interesting these guys named the video “flowing with the boys,” as that’s also how I think of it.

All is flow— Panta Rhei, as Greek philosopher Heraclitus is reputed to have said. You can’t step in the same water twice, as both you and the water have changed.

All is flow, says psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced me-HIGH chick-sent-me-HIGH-ee). In Flow theory, he describes a mental state of complete immersion and engagement in an activity. Individuals experience deep focus, a sense of control, and intrinsic motivation, often losing track of time. Csikszentmihalyi identifies several key components that contribute to the flow experience, to include a good challenge-to-skill balance, clear goals and performance feedback, and a loss of self-consciousness— literally merging with task and environment. Flow can occur during various activities, usually including physical activity, creative endeavors, and enjoyable pursuits.

All is flow, says Physics professor and discoverer of the Constructal law Dr. Adrian Bejan. It is a principle of design in nature that states: for a system to persist over time, it must evolve to provide easier access to flows. It applies broadly across physics, biology, and social systems, explaining why river basins, vascular networks, and even traffic patterns optimize their configurations to minimize resistance and maximize efficiency. This law unifies seemingly unrelated phenomena by emphasizing that systems naturally develop designs that improve their ability to flow and function over time.

All is flow, says godfather of process philosophy, Alfred North Whitehead. It’s less thinking about things, about objects, and more thinking about fluids, currents, interconnections, and relationships.

Taoism is big on flow. Lao Tzu's teachings in the Tao Te Ching emphasize flow, harmony, and the natural way of things, often referring to the concept of "Wu Wei— effortless action or non-striving.

This flowing in-between-ness is where the magic lives.

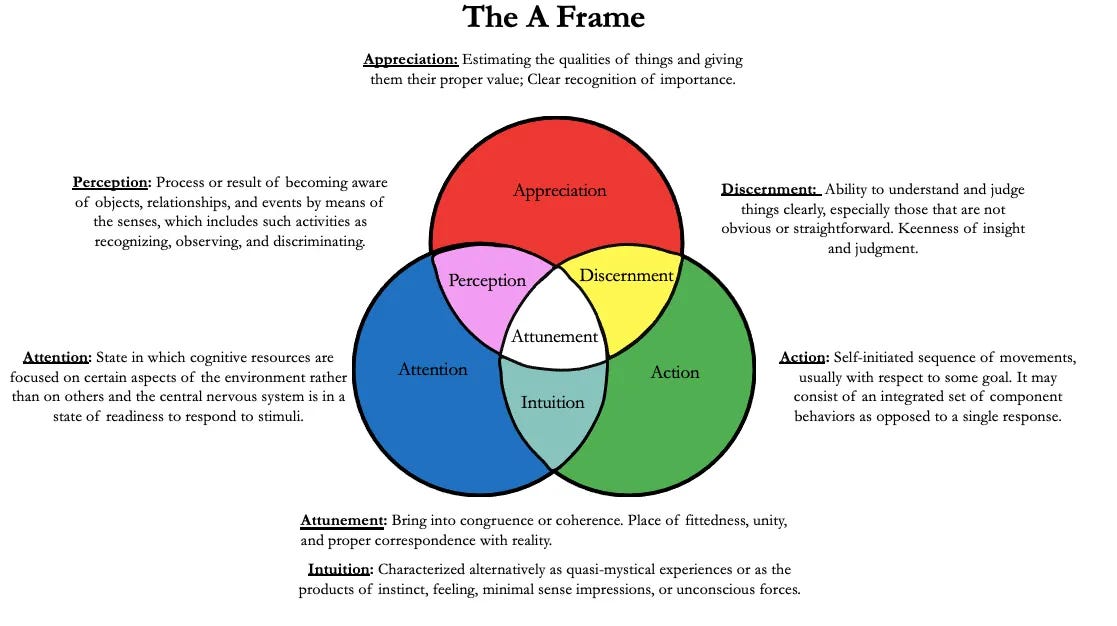

This is what I’m hunting for when I talk about Attunement.

When I’m describing Attunement, I’m describing Flow.

This is what Cliff Kimber talks about—I can’t wait to read his forthcoming Born to Flow.

This is what John Boyd is getting at with the OODA loop that is not a loop— in particular the iterative, recursive, nonlinear orientation and reorientation.

In Stealing Fire, Jamie Wheal describes precisely this sort of group flow in the first chapter and parts thereafter.

After a few years of training, when at long last I clawed out a better understanding of the craft, CQB went from white-knuckled stress to joyous play. I don’t want to detract from the seriousness of the endeavor, but it became a lot of fun. It’s enjoyable to roll through the house with a dozen of your mates, solving problems and overcoming the challenges the cadre prepared to test your group.

It became a place to Flow, within myself and as a member of a team. During my platoon commander tour, I used to tell my platoon I wanted us collectively to be a “porcupine moving through space,” which earned me no end of ribbing/ball busting.

While training in a Kill House gives you Skin in the Game, going into a building in combat brings Soul in the Game.3 Each move, each decision, has life or death implications for you and your teammates.

How can I best support my buddy?

Be a good number two man.

Clear your corner.

Read the room.

After hundreds, sometimes thousands of hours training together, you attune to each other and the environment, and move as one.

This flowing in-between-ness is where the magic lives.

Currere Certamen Tuum

In the special operations community, we call it Close Quarters Battle (CQB) or Close Quarters Combat (CQC). It refers to engagements in confined spaces where combatants confront each other at very short ranges. These situations are typically characterized by rapid, high-intensity conflict requiring swift, decisive actions.

I don’t want to get in the weeds with tactics, because everyone has their own opinion. Here’s a primer on two main ways to clear a building.

In his work, Nassim Taleb describe three levels of personal involvement and accountability. No skin in the game refers to individuals or entities who face no real risk for their actions or decisions, often benefiting while others bear the costs (policymakers or executives insulated from the consequences of their policies). Skin in the game involves shared risk, where individuals are directly affected by the outcomes of their decisions, ensuring accountability and fairness (entrepreneurs or citizens). Soul in the game goes beyond risk-sharing, representing a deeper commitment where individuals act out of passion, integrity, or a sense of purpose, driven by values rather than personal gain (soldiers, artists, those pursuing their calling). Soul in the game is taking a bullet for someone else, or at least risking it.

Dude, were we at ST4 at the same time? I got there in ‘02

Fabulous essay Adam! 👏 FLOW is one of the top 10 psych concepts I have ever encountered. Such a profound neurobiological event related to learning, high performance and ... happiness!

When I advised people about finding their optimal career path, I put "flow" at the center of the conversation:

https://bairdbrightman.substack.com/p/finding-your-right-work