Welcome to A Mindful Miscellany, where we focus on sense-making and story-telling in the turbulent twenties. We are devoted to cultivating the conditions for sagacity to emerge, like Punxsutawney Phil, from his wintry lair. No guarantee that it will happen, but we are over the moon when it does. I humbly serve as your blundering yet intrepid wayfinder, touching the elephant of reality in most unseemly ways. Bio here.

The most recognized version of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, at least in the West, comes through the poem "Der Zauberlehrling," by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1797. Often the basis for modern adaptations of the tale, the basic motif is of an uncontrollable magical force unleashed by an overconfident or inexperienced practitioner. It is a common theme in many stories and legends, such as the dialogue The Lover of Lies , written by Loukianos of Samosata in ancient Greece.1

The tales revolves around a young apprentice who, in his master's absence, attempts to use magic to perform his chores. He succeeds in enchanting a broom to do the work for him, but he cannot control the spell. As a result, the broom continues to fetch water until the house is almost flooded. Unable to stop the broom, the apprentice splits it in half with an axe, but each half then becomes a whole new broom that continues the task, doubling the problem. The chaos goes on until the master returns and swiftly breaks the spell, teaching the apprentice a lesson about the dangers of meddling with forces beyond his understanding.2

The most famous, pop culture adaptation of "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" is Disney's "Fantasia" (1940), where Mickey Mouse plays the role of the apprentice. The music for this version is Paul Dukas' symphonic poem "L'apprenti sorcier" (1897), also based on Goethe's poem.

This story is on my mind because I recently watched and listened to two interviews that referenced it, both within the span of a few hours. When that happens, I feel like I should slow down and attend closer.

The first was Dr. Iain McGilchrist speaking to Damien Walter, former Science Fiction critic for The Guardian and current host of the Science Fiction Podcast. Walter, in true Metamodern fashion, both sincerely and ironically refers to himself as “The Joe Rogan of Science Fiction.” They connect McGilchrist’s work (Which I talk about in my 3 part series on Agent/Arena/Agency here) to the power of Mythic stories.

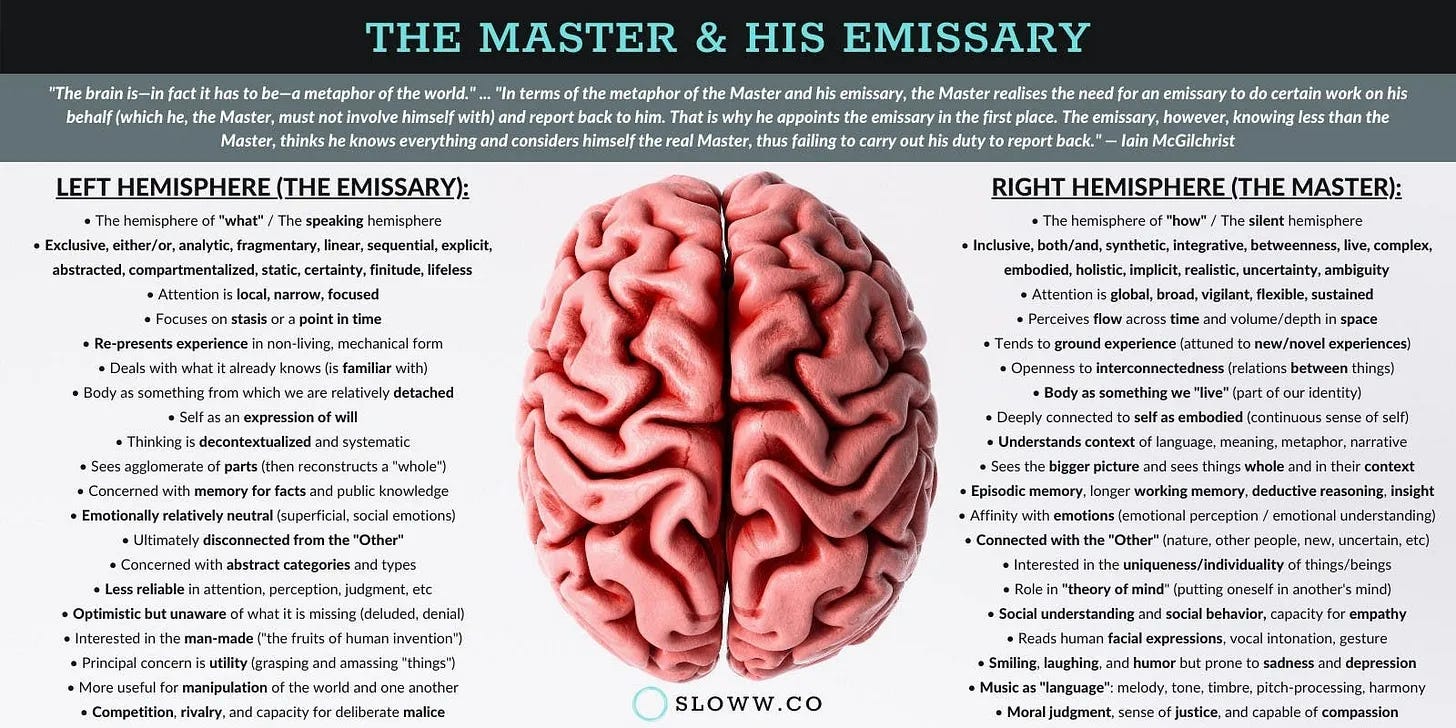

The main thrust of McGilchrist’s work is that brain hemispheric differences are about attention— one part is discrete and focused, the other diffuse and global.3 Here is a great post from Perspectiva that takes up the challenge of summarizing his work, and a helpful graphic from Sloww.co:

According to McGilchrist, the left hemisphere is more analytical, linear, and focused on details. It excels at categorization, language, and logical reasoning. The left hemisphere breaks down the world into smaller parts, allowing for a more focused and specific understanding of individual elements.

On the other hand, the right hemisphere is characterized by holistic thinking, creativity, intuition, and an awareness of the interconnectedness of things. It focuses on the "bigger picture" and processes information in a more intuitive and simultaneous manner. The right hemisphere is associated with the appreciation of art, music, and spiritual experiences.

Bottom line— we have too much left hemisphere going on today in our WEIRD world, and not enough right hemisphere. This is not to say the left hemisphere is bad— it is responsible for many of the wonders of the modern world. But it must be employed in proper relation to the right. Here’s the video:

The second interview is from The Center for Humane Technology, a policy advocacy group run by Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, discussing what tales of mythology and magic can teach us about the AI race. Their guest, mythologist Josh Schrei, explains how looking at foundational cultural stories could guide ethical tech development.

Not mentioned in the episode but noteworthy, Harris and Raskin propose “Three Rules” for Humane Technology:

RULE 1: When we invent a new technology, we uncover a new class of responsibility. We didn't need the right to be forgotten until computers could remember us forever, and we didn't need the right to privacy in our laws until cameras were mass-produced. As we move into an age where technology could destroy the world so much faster than our responsibilities could catch up, it's no longer okay to say it's someone else's job to define what responsibility means.

RULE 2: If that new technology confers power, it will start a race. Humane technologists are aware of the arms races their creations could set off before those creations run away from them – and they notice and think about the ways their new work could confer power.

RULE 3: If we don’t coordinate, the race will end in tragedy. No one company or actor can solve these systemic problems alone. When it comes to AI, developers wrongly believe it would be impossible to sit down with cohorts at different companies to work on hammering out how to move at the pace of getting this right – for all our sakes.

I should note that this arms race, mentioned in rules 2 and 3, is what we’re talking about when we say things like “multi-polar traps,” because the system itself (which some personify with the title “Moloch”) is driving humans and their groups into self-destructive spirals of behavior.

This story, this Sorcerer’s Apprentice story, is an old one, and it has remained in our collective memory for a reason. Like the tale of Pandora’s Box, it has utility. Last summer, the movie Oppenheimer explored themes of fear, regret, and guilt in the creation of an existential risk type technology of the nuclear bomb.

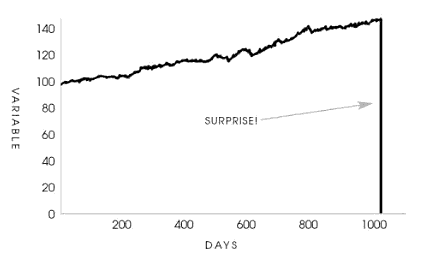

One counter-argument might be the notion that “we haven’t done it yet,” meaning that our inexorable technological progress has not resulted in a catastrophe. Yet. But this runs into the epically snarky author Nassim Taleb’s parable of the Turkey:

Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race “looking out for its best interests,” as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief.

The Black Swan, by Nicholas Nassim Taleb

I don’t know what the answers are. I don’t think the sky is falling.

We are going to muddle our way out of this. We’re resilient that way.

But I do hope “we,” as in we in the West, can bring a little more right hemisphere into our lives. This normally involves reconnecting with some Indigenous ideas about reality.

Today we use the word “myth” to mean something false, as in “five myths about rollerblading in neon pink speedos!”

But the older meaning of “myth”, comes from the Latin and Greek "mythos.” This definition includes “anything transmitted by word of mouth, such as a fable, legend, narrative, story, or tale, having a significant truth or meaning for a particular culture, religion, society, or other group.”

I hope we can remember some of these old tales, and the deep wisdom embedded within them, as we grapple with new technologies and new situations.

Have a great week, everyone!

https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/2017/04/29/the-ancient-greek-sorcerers-apprentice/

This actually sounds like Bostrum’s “paperclip maximizer” now that I think about it.

It’s important to note, this is not the usual pop science “left brain math, right brain creativity.” Both hemispheres do both of those topics, and Dr. McGilchrist ground his claims with thousands of research studies into hemispheric differences.

Utterly brilliant, but probably a lot for some folks to bite off and chew thoroughly. Love what broad reach you have, in all you discuss with your sure hand, but winnow down or break into smaller pieces for some of us who are not quite as capable. Thanks for the use of the hall