“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.” —Robert A. Heinlein, Time Enough For Love

Welcome to the Renaissance Humans Newsletter, where I focus on sense-making and story-telling in the turbulent twenties. The Renaissance (“rebirth,” in French) spanned from the 14th to the 17th century and marked a period of cultural, artistic, and intellectual renewal in Europe. A Renaissance Human fosters curiosity, creativity, critical thinking, and character in a journey of never-ending learning. They cultivate Mind, Body, and Spirit, in service of Community, and oriented to the Transcendentals.

Story isn’t collapsing as we transition to new mediums of communication, but Depth is—our ability to focus, see nuance, and introspect.

Ted Gioia’s recent essay “The Decline of the Novel” gave me the inspiration to work on this, which has been bothering me for a bit. It was lurking in the interstices, waiting to come out.

At the end of his essay, Gioia concludes, “Stories hold societies together. To some extent, they hold people together. That was true in Homer’s day and it’s still true today. If the stories collapse, all the king’s software and digital devices won’t even begin to put us together again.”

Let’s focus on the possibility—no, the probability, that our primarily printed word culture is beginning a long transition to audio and video.

As we know from reading, listening, and/or watching our Daniel Schmachtenberger and Tristan Harris, technology is not neutral. It brings a whole set of baggage with it.1

As Schmachtenberger relates, the plow brings a new relationship to the earth, and the subordination of animals to this novel implement. When we yoked an animal in servitude, our relationship to the natural world shifted. We couldn’t be animists any longer— we had to think up new ontological frameworks to reconcile our changed situation.

I brought up waves of communication last week, as mentioned in Martin Gurri’s Revolt of the Public. These were developed by folks like Harold Innis and Marshall Mcluhan:

Oral Communication (Prehistoric to Early Civilization): First form of communication. Knowledge, culture, and traditions were passed down through spoken language and storytelling. No written records existed, so people relied on memory and verbal transmission.

Written Communication (Around 3200 BCE to 15th Century): Invention of writing systems— cuneiform and hieroglyphics, which revolutionized how information could be stored and shared. Papyrus, parchment, and paper increased the ability to preserve knowledge over long periods.

Print Communication (15th Century – 19th Century): The Gutenberg press in the mid-15th century marked a major breakthrough—Mass production of books, pamphlets, and newspapers allowed for widespread dissemination of knowledge, contributed to the Renaissance, Reformation, and Enlightenment.

Electronic Communication (19th Century – Late 20th Century): Began with the invention of the telegraph, followed by the telephone, radio, and television. These technologies enabled instantaneous communication over long distances, changing how news and information were shared globally. Radio and TV spread propaganda and advertising, as Adam Curtis so beautifully lays out in The Century of the Self documentary series.

Digital Communication (Late 20th Century – Present): Advent of the internet, computers, and mobile technology. Communication is now faster, more interactive, and global. Social media, emails, instant messaging, and video conferencing transformed how people interact, creating a more connected world.

What are the implications?

To find out, I asked one of our robot overlords, Chat GPT. At this point these Large Language Models (LLMs) are like Djinns. I noticed my Chat GPT has started to link search queries together and answer in a more synthetic fashion, which is mildly unnerving. It references things I asked weeks or months ago when replying.

I asked it to run the medium of smartphone-enabled social media through Marshall McLuhan’s Tetrad. If you’re not familiar, McLuhan was a brilliant media theorist, known for the catchphrase the medium is the message, and its much more hilarious cousin, the medium is the massage.

His key insight is that the medium itself, not just the content it carries, has a large impact on society— how we take in information. McLuhan argues that the characteristics of a medium shape and control "the scale and form of human association and action.” It influences how we think and interact with each other. Our default setting as humans is to focus on the content of a medium, and we tend to overlook the structural changes it introduces into our lives and society.

Importantly, Mcluhan saw media as "extensions of ourselves" that alter how we use our senses to perceive the world. Different types of media engage different senses and cognitive processes.

McLuhan’s Tetrad is a way to unpack the changes a new piece of technology brings. Here’s what it looks like:

Question: Using Marshall Mcluhan's tetrad, how is smartphone enabled social media changing how humans communicate? What does the use of social media on smart phones obsolesce, retrieve, reverse, and enhance?

Answer: Marshall McLuhan's tetrad of media effects offers a powerful framework to analyze how technological advancements impact society and culture. The tetrad asks four key questions about a new technology: what does it enhance, obsolesce, retrieve, and reverse into when pushed to its limits? Applying this to smartphone-enabled social media:

1. Enhances

Smartphone-enabled social media enhances human communication by increasing the speed, accessibility, and reach of interactions. It allows instant, global communication through text, images, video, and voice. This communication becomes multimedia-rich and instantaneous, amplifying the way we connect, share ideas, and form communities.

Real-time interaction: People can share and consume news, events, or opinions as they happen.

Democratization of voice: Individuals, regardless of background, can publish content to the world, gaining visibility outside of traditional media channels.

Global connectivity: People can maintain and form relationships across geographical boundaries, creating digital communities and networks of influence.

2. Obsolesces

It obsolesces or diminishes the need for older, slower forms of communication such as:

Traditional print media: Newspapers and magazines have seen declines as people get their news and information from social media feeds.

Long-form communication: Letters, in-depth phone conversations, or even long-form journalism are often replaced by the immediacy and brevity of status updates, tweets, or quick exchanges on messaging platforms.

Face-to-face communication: In some cases, smartphone social media has reduced the frequency of direct, physical social interactions, as people often prefer to connect online.

3. Retrieves

It retrieves elements of more ancient communication forms, especially oral and visual traditions:

Oral communication: Social media brings back a form of conversational, spontaneous dialogue reminiscent of pre-literate societies, where communication was rapid, unfiltered, and more ephemeral. Platforms like TikTok or Instagram Stories favor transient, performative, oral-visual formats.

Pictorial communication: The dominance of visual media (photos, emojis, memes) revives a kind of visual storytelling that recalls ancient cave paintings, symbols, and hieroglyphics, as users communicate in brief, symbolic, image-driven ways.

4. Reverses

When pushed to its extremes, smartphone social media reverses into isolation and fragmentation of communication (Items bolded for emphasis):

Echo chambers and polarization: While social media connects, it also creates echo chambers where people only engage with like-minded views, reversing into polarized, fragmented societies with diminished open dialogue.

Attention scarcity: The constant barrage of information can overwhelm and reverse into shorter attention spans, where meaningful, sustained conversations are harder to maintain.

Alienation: Paradoxically, as more people spend time communicating online, they may experience increased loneliness or a sense of superficial connection, reversing the intent of deeper social bonds.

In sum, smartphone-enabled social media enhances communication by making it instantaneous and global, obsolesces older forms of slower communication, retrieves visual and oral traditions, and when pushed too far, reverses into fragmentation and social isolation.

This is where I must pause and make a plug for Mike Judge’s tour de force masterpiece, from those simple seeming days of the early aughts. What was comedy has morphed into cautionary tale:

“You want to put toilet water on the crops?”

Which brings me back to the novel. What does the novel (and its relatives— short stories and nonfiction vignettes) give us that we can’t get in a movie?

Interiority.

The mental or emotional experiences of an individual. I mean introspection, self-awareness, and a rich inner world that stands in contrast to how someone acts in the outside world.

Megha Lillywhite made this point over the summer, in her usual snarky fashion.

“The video can convey what we look and sound like, but never our philosophic world, our hopes and our dreams. It is a mirror only of our physical world and if it tells us anything about our spiritual one, it is indirectly and by accident, like the patterns of basket weaving from an primal tribe might tell us how they worshipped the forest as a God. In our time period, perhaps, our media will reveal how we worship girls in face filters doing makeup while repeating feminist talking points.”

The novel is a recent invention— only a few hundred years old, and it’s already beginning to wane in popularity, as humans lose the attention span to engage with the written word. Accessing the thoughts of another allows us to live multiple lives within our own sparse allotment of years. If I get to see interiority, either in a memoir or fictional character, I access all of that discernment, all of that Vervaekian Recursive Relevance Realization.

In plain speak, that means I get to see how you or a fictional character navigates a given environment, context, or situation.

Can you get something similar with movies/shows? Yes, to a degree. You can project a voiceover with character thoughts and/or brutally honest journal entries, like Bridget Jones’s Diary does.

But it’s shallower than a novel, interiority-wise. Purposefully, because of the structural limits of the medium. The visual medium is prioritizing different things than character interiority. Movies and shows give you aesthetically gorgeous settings, active characters, and powerful dialogue. But you don’t get the depth—you rarely get to see how characters came to the decision they did, how they internally deliberated. In a film or show, you can’t build the nuances of a relationship to the depth of a novel. Perhaps you can get close, over several seasons of a show. Even then you can’t go as deep as a novel.

But there’s another thing novels do differently than shows and movies. You get to co-create the world of a novel with the writer, in your mind. My version of Sherlock— the version in my mind from reading the books, is different than the movie and television versions of Sherlock, as well as the version in your head. We all get to use our imaginations to make the world of the story come alive— every tendril of smoke, play of light, smell of burning trash. A movie or show can portray an amazing scene, but it doesn’t leave me anything to do, save passively observe it. At least a video game will give you agency in the story, a place to have an impact on what happens, like one of those amazing Choose Your Own Adventures.

I’m not shitting on movies and shows. I love them. I enjoy losing myself in a well created work. Homecoming was a brilliant audio only story, before it was an FX series, in the vein of old timey radio shows.

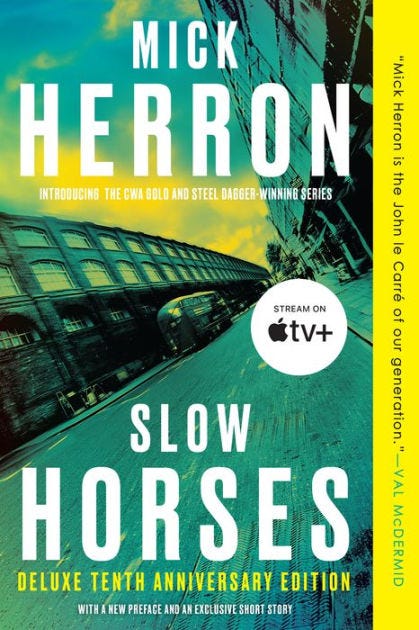

My wife has read every Mick Herron novel, while I have not. The books provide a depth of backstory and interiority that the show can’t. One thing she raised was the difference between reading and watching or listening to a story. You can’t multitask when physically reading a book.2 Audio and visual mediums allow for watching/listening while engaged in other tasks. Reading allows humans to strengthen our ability to focus in ways the other mediums do not.

Depth.

Not reading the books hasn’t stopped me from enjoying the hell out of Slow Horses.

I am simply trying to highlight what novels give us that the visual medium cannot.

I don’t think Story will Collapse, as Gioia hints at in his piece.

I don’t think the novel will die either—most likely it’ll just become a niche pursuit, like the theater.3

I think Story will continue its long line of transformations.

People warned of catastrophe before, when we shifted communication paradigms, and we’ve managed to stay afloat as a species.

Socrates was certain that writing things down was doing to destroy humans minds, and their impressive ability to recall and orally recite thousands of lines of epic poetry.

Victor Hugo, of The Hunchback of Notre Dame fame, argued in “This will kill that,” books created by the printing press would overtake architecture as the primary way humans conveyed culture and values.

I’m sure there was someone lamenting the shift to radio and television back in the day.

The decline of the novel is related to a dramatic decline in reading in general, whether fiction or nonfiction.

Audio and visual mediums are consuming the attention of humans, who increasingly prefer this to sitting in the depth and time commitment of a book or novel.

While I’m not concerned that Story will collapse, I am concerned about whether the audio/visual medium can adequately communicate the requisite level of complexity the printed word does.

Can it convey the depth of knowledge required to maintain this modern, global civilization? I don’t know.

Nicolas Carr in The Shallows is not optimistic. Here’s a YouTube Short explaining his argument, hilariously proving the point.

Carr’s book explores how the internet is changing our brains and cognitive processes. He argues the internet is rewiring our brains to be more distracted and less capable of deep, focused thought. Constant internet use may be reducing our capacity for concentration, contemplation, and reflection. While the internet provides numerous benefits, it's also changing how we process information in potentially problematic ways. Carr advocates for a more balanced approach to technology use, recognizing both its benefits and potential drawbacks.

I could be totally wrong about this. I hope I am.

Maybe the reading apocalypse will reverse itself, or normalize into a happy medium mixture of reading, watching, and listening.

Maybe we’ll be totally fine, learning everything through videos.

Maybe we won’t lose the nuanced transmission of internal complexity books give us, essential to keeping up with the external complexity of the modern world, as Rebecca Costa argues in The Watchman’s Rattle.

Maybe it will, indeed, all buff out.

Personally, it’s not going to change anything I do. I will continue to acquire books until I reach Umberto Eco status.

And I will continue to write because I have to.

Currere Certamen Tuum

This would include things like rivalrous dynamics, or arms races— best exemplified by one of my favorite books to read my spawn, The Butter Battle Book, by Dr. Seuss.

Although I recently saw a woman in my neighborhood walking her dog and reading a physical book, which was super impressive.

It brings me no joy to say this. I’ve been waiting my entire life to write novels. I’m in the query trenches with a novel now.

Well said. Interesting that Chat GPT didn't include the novel in its assessment, perhaps because it doesn't consider it a communication medium like long-form journalism.

Also, while I agree that the popular novel is only a couple centuries old, I'm not sure if there's a useful distinction to be made between modern novels and something like the Satyricon or the Golden Ass. Granted, the pool of readers back then was shallower, so maybe there wasn't much penetration.

Very thorough analysis of several trend lines. And a deep one. The act of thinking it through and writing it, belies your thesis that we may be losing our ability to create meaningful stories. As long as we are willing to be honest, we will retain our ability to integrate our tale with our tail.