Welcome to Renaissance Humans, where I focus on sense-making and story-telling in the turbulent twenties. In this liminal, time between worlds, a time of networks and nonlinearity, we need all hands on deck, as my grandmother used to say. A Renaissance Human cultivates curiosity, creativity, critical thinking, and character in a journey of never-ending learning. They develop Mind, Body, and Spirit, in service of Community, and oriented to the Transcendentals.

My name is Adam. You can learn more about me here.

“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.”

― Edward O. Wilson, The Origins of Creativity, 2017

I’ve wanted to read Neil Postman’s Technopoly for a few years now, ever since I read Amusing Ourselves to Death. So I was quite chuffed and gruntled1 when one of my professors assigned it for class.

It did not disappoint.

In Technopoly, Postman argues contemporary society has allowed technology to dominate every aspect of human life—reshaping values, beliefs, and cultural practices in its image. He defines "Technopoly" as a state in which technology moves beyond being merely a tool, becoming instead an all-encompassing worldview that marginalizes traditional moral, religious, and humanistic narratives. Postman critiques the manner in which this technocentric ideology prioritizes efficiency, quantification, and progress at the expense of wisdom, tradition, and genuine human connection.2 Ultimately, he warns that unless society consciously restores critical reflection and moral discourse regarding technology, humanity risks losing control over its own culture and meaning-making capabilities. Postman divides human history into three eras:

Tool-Using: Pre-Enlightenment, those good old days when depending on who you ask, we were either noble savages or life was nasty, brutish, and short.

Technocracies: 1561 to about 1925. Basically, the Enlightenment to the Scopes Monkey trial in the United States. The trial ended with teacher John T. Scopes being found guilty of teaching evolution in violation of Tennessee law, highlighting the national conflict between science and religion.

Technopolies: 1925 to present day. He asserts the United States is the only true Technopoly at the time of writing3, but if he were alive today he might add Europe and China into the mix.

His arguments remind me of Marshall McLuhan, which makes sense, since Postman was one of his disciples. Like McLuhan, he notes the ways the various stages of communication technology impact how humans perceive reality. Postman asserts that in a Technopoly, the experts are the priests, a new clerisy of bureaucracy. This connects to Matt Crawford’s work on his Archedelia substack, and his book The World Beyond Your Head. Crawford critiques what he terms “The Managerial State”, the tech-focused expert class who seek to run society.

Characteristics of Technopoly

1. Technology Becomes Self-Justifying. In a technopoly, technology no longer serves cultural values. Instead, it defines them. The question is no longer “Should we use this?” but “How soon can we implement it?” New technologies are adopted without ethical or cultural debate.

2. Information is Decontextualized. Technopoly floods society with information, but disconnects it from wisdom or meaning. More data is equated with more knowledge, even if it’s irrelevant or misleading. Institutions are obsessed with metrics, statistics, and systems that lose the human story.

3. Experts Replace Elders. Authority shifts from community and tradition to technical experts and data analysts. Problems are reframed as technical, not moral or social. The “expert class” is seen as the only source of legitimate answers.

4. Technology Solves All Problems. There is an implicit faith that every human issue has a technological solution. Human judgment, tradition, and ethics are seen as inefficient or outdated. Non-technical knowledge (like religion, art, humanities-type content) is devalued.

5. Culture Submits to Technology. In a technopoly, society doesn’t just use tools—it submits to their logic. Technologies reshape language, values, education, even our sense of self. We come to serve the needs of technology, not the other way around.

In short, Postman warns Technopoly undermines meaning, weakens critical thinking, and sacrifices wisdom for efficiency. It leads to cultural amnesia, where we forget how to ask, “What is this technology for?” and “Should we even use it?”

Postman admits he doesn’t have the answer to this problem, but he does recommend becoming what he terms a “loving resistance fighter.” He writes:

Those who resist the American Technopoly are people who pay no attention to a poll unless they know what questions were asked, and why; who refuse to accept efficiency as the pre-eminent goal of human relations; who have freed themselves from the belief in the magical powers of numbers, do not regard calculation as an adequate substitute for judgment, or precision as a synonym for truth; who refuse to allow psychology or any “social science” to pre-empt the language and thought of common sense; who are, at least, suspicious of the idea of progress, and who do not confuse information with understanding; who do not regard the aged as irrelevant; who take seriously the meaning of family loyalty and honor, and who, when they “reach out and touch someone,”4 expect that person to be in the same room; who take the great narratives of religion seriously and who do not believe that science is the only system of thought capable of producing truth; who know the difference between the sacred and the profane, and who do not wink at tradition for modernity’s sake; who admire technological ingenuity but do not think it represents the highest possible form of human achievement.

With those that in mind, let’s look at some principles and concepts that might help us shine a light on the hard-to-see impacts of technology.

Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin5, the creative force behind The Social Dilemma documentary, have proposed three rules for humane technology. They are:

RULE 1: When we invent a new technology, we uncover a new class of responsibility. We didn't need the right to be forgotten until computers could remember us forever, and we didn't need the right to privacy in our laws until cameras were mass-produced. As we move into an age where technology could destroy the world so much faster than our responsibilities could catch up, it's no longer okay to say it's someone else's job to define what responsibility means.

RULE 2: If that new technology confers power, it will start a race. Humane technologists are aware of the arms races their creations could set off before those creations run away from them – and they notice and think about the ways their new work could confer power.

RULE 3: If we don’t coordinate, the race will end in tragedy. No one company or actor can solve these systemic problems alone. When it comes to AI, developers wrongly believe it would be impossible to sit down with cohorts at different companies to work on hammering out how to move at the pace of getting this right – for all our sakes.

Our tools are making us more and more disconnected, alienated, separated, and abstracted from the world. While they bring wondrous and legitimately miraculous gifts, they create a host of second and third order impacts—some of which take years to reveal themselves.

Technology has moral implications.

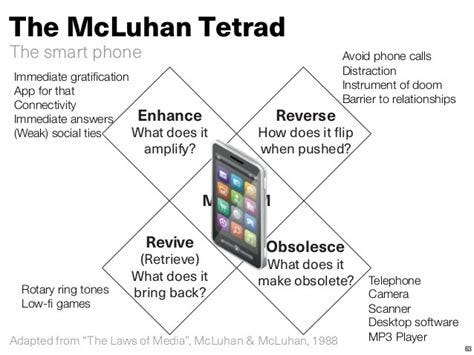

That’s one thing we often forget, because this fact is embedded within the tech, influencing us like a magnetic field. And it’s hard. It takes effort to think critically about technology. That’s why something like McLuhan’s Tetrad is so valuable. It helps unmask what a given piece of tech is going to do to individual humans and our societies.

I talk about the Tetrad in greater detail in this post:

Not Story Collapse — Depth Collapse

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, d…

So, what do we do?

For most of us, it’s not realistic to forsake technology—to go back to some imagined golden age of when we were pure. That’s fantasy. We’ve been tool-using creatures from the beginning.

But it is about deciding what kind of society we want, what kind of humans we want to be, and putting tech in service of that—rather than us serving the algorithms.

That involves foregrounding the sacred, rather than the market or technology.

But whose idea of sacred? Aye, therein lies the rub.

Simple, but not easy.

Currere Certamen Tuum

"Gruntled” obviously being the opposite state from being disgruntled.

I think you know where I’m going with this…. (coughs, mutters McGilchristLeftHemisphere under breath)

Again, in the fricking 1990s!

1990’s AT&T advertising slogan for telephones.

Harris worked at Google as an ethicist before parting ways, and Raskin gifted humanity with the “infinite scroll” feature for social media. I assume he is devoting the rest of his life to atoning for that lovely invention.

Thank you for this Adam. I appreciate that the critique was so comprehensive and yet it did not invoke neoliberalism, which I find is so often pointed to as the culprit for the type of declines you discuss. Not that it's wrong to point to neoliberalism, but it's so often brought up as the culprit that the meaning gets lost and the pathways to change get murky.

Excellent writing on an important topic, Adam! 👏

As a psychologist, I strongly agree with "refuse to allow psychology or any “social science” to pre-empt the language and thought of common sense". Referring to fear as "anxiety" isn't just different; it's worse.

I would distinguish between technology and science, but too complicated to go into in a comment. Maybe a topic for a future essay? Thanks for the inspiration!